Here, Explains why Covid deaths have varied so greatly across countries

No one would describe 2020 as normal. The corona virus disrupted travel, employment and livelihoods. It pushed countries into lockdown, forcing people to change how they lived.And it infected millions of people, resulting in many getting severely ill and death. The high number of deaths in 2020 was completely abnormal.

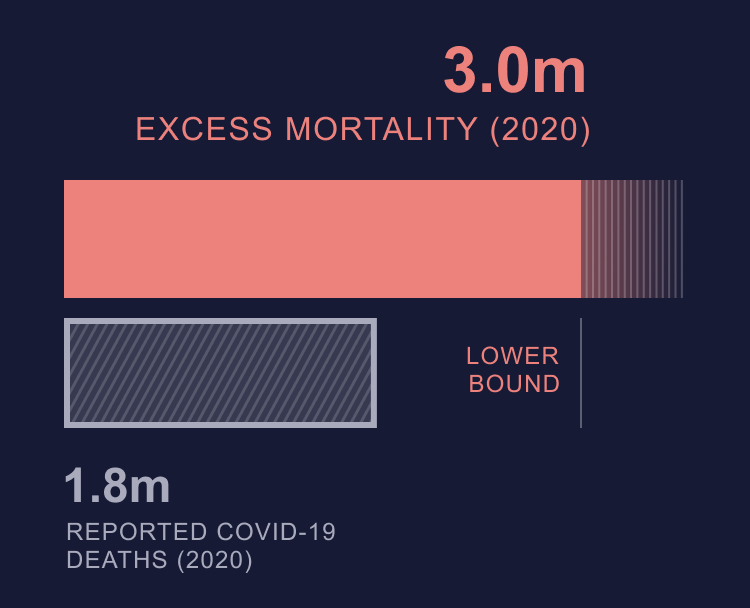

“Excess mortality” is how this abnormality is measured. It’s the number of deaths – from all causes – that occur during a crisis that’s beyond what would be expected in typical times. When looking across a sample of 79 high-, middle- and low-income countries, overall there were 3.7 million more deaths in 2020 compared with the average for 2015-19 – an excess of 13%.

This figure reflects not only official COVID deaths, but those caused by the virus yet not recorded as such. It also includes deaths that might have been prevented if the pandemic hadn’t happened. Those caused by cancers or strokes going untreated due to healthcare systems being overwhelmed.

Government responses

Contrary to what you would think, countries with the longest. Most stringent lockdowns were likely to have higher rather than lower excess mortality. Governments that used them did so because they failed to act in time. They implemented delayed lockdowns across their entire countries, underestimating the virus and prioritising economic order.

Chile, El Salvador and Peru had the most stringent lockdowns, and all recorded a rate of excess mortality that was 20% or higher. In contrast, lockdown stringency in Norway, Iceland and Finland was low. Their excess deaths didn’t exceed 3%.

Having a strong test, trace and isolate system was strongly associated with fewer deaths. For example, Taiwan recorded just 1.6% excess deaths and 0.03 COVID deaths per 100,000 people during 2020 and had one of the world’s most efficient test-and-trace systems.

Location, location, location

Geographically isolated island countries, such as New Zealand and Iceland, were more likely to record low excess mortality. They were better placed to control their borders and detect people infected with Covid on arrival.

Several Asian countries tended to have strong test-and-trace capacity. This frequently resulted in lower excess mortality (China and Japan being examples, alongside Taiwan). These countries managed to contain the pandemic in 2020 by conducting comprehensive contact tracing for all COVID cases.

In contrast, Central and South American countries tended to have weak test-and-trace capacity. Four of the five worst hit countries were in Latin America (Mexico, Nicaragua, Ecuador and Bolivia). Countries with the longest periods of stay-at-home orders also tended to be in Central and South America.

How to do better next time

During the first year of the pandemic, most governments ended up implementing punishing measures to try to control the virus, such as lengthy lockdowns and personal restrictions.

Governments could achieve better health outcomes in future by making sure that their responses are more timely, kicking in before the infection rate escalates. They could also make disease control more effective by improving test-and-trace capacity and boosting the preparedness of health systems, by providing sufficient funding and making services accessible to the whole population.

Even now, vaccines cannot be relied on as the sole solution to the pandemic. To keep excess death down, much more needs to be done to stop healthcare systems from being overwhelmed by generously supporting them and enhancing test-and-trace systems.