The calendar helps to give us a map of the shifting revolutions of the seasons, ordering our days. But how did it come about?

For something that’s meant to lend order to our lives, the modern Western calendar has a messy history. The mess, in part, comes about because of the difficulty of co-ordinating the orbits of celestial bodies .

The year measured by the earth’s orbit around the sun is roughly an unruly 365.2422 days. The moon is likewise not a fan of whole numbers. In the space of a year, there are around 12.3683 lunar months. Societies have traditionally tried to make sure that the same seasons lined up with the same months.

Ancient calendars from Mesopotamia, for example, co-ordinated months and seasons , a process called intercalation. In some lunar systems, though, the months can wander through the seasons – this is the case for the Islamic Hijri calendar.

The solar calendar of ancient Rome gives rise to our modern Western calendar. The Julian calendar, named after Julius Caesar’s reforms of 46/45 BCE, approximated the solar year to 365.25 days . That left a rather annoying 11 and a bit minutes unaccounted for. More on those minutes later.

The Julian calendar also left us a legacy of months in strange positions. Our eleventh month, November, derives from the Latin for the number nine, a result of moving the start of the year from March to January.

New months and names were juggled and rejigged to match the mechanisms of power. August, for example, is named for the Emperor Augustus. As the great Australian historian Christopher Clark has put it: “as gravity bends light, so power bends time”.

Christian time keeping

As the Roman empire shifted into the world we now call the middle ages, the power that bent time most successfully was that of the church. But just as in the present, the church was a multiplicity of intersecting powers with local and regional differences, and with a variety of internal identities and struggles. The start of the year, for example, could vary widely across medieval societies.

Unreasonable nature

It’s easy to feel lost in time. The calendar helps to give us a map to the shifting revolutions of the seasons, the shape of our lives, and the larger arcs of history. But while we are placed in the matrix of calendar time, we also make it: could we do better than the Gregorian calendar?

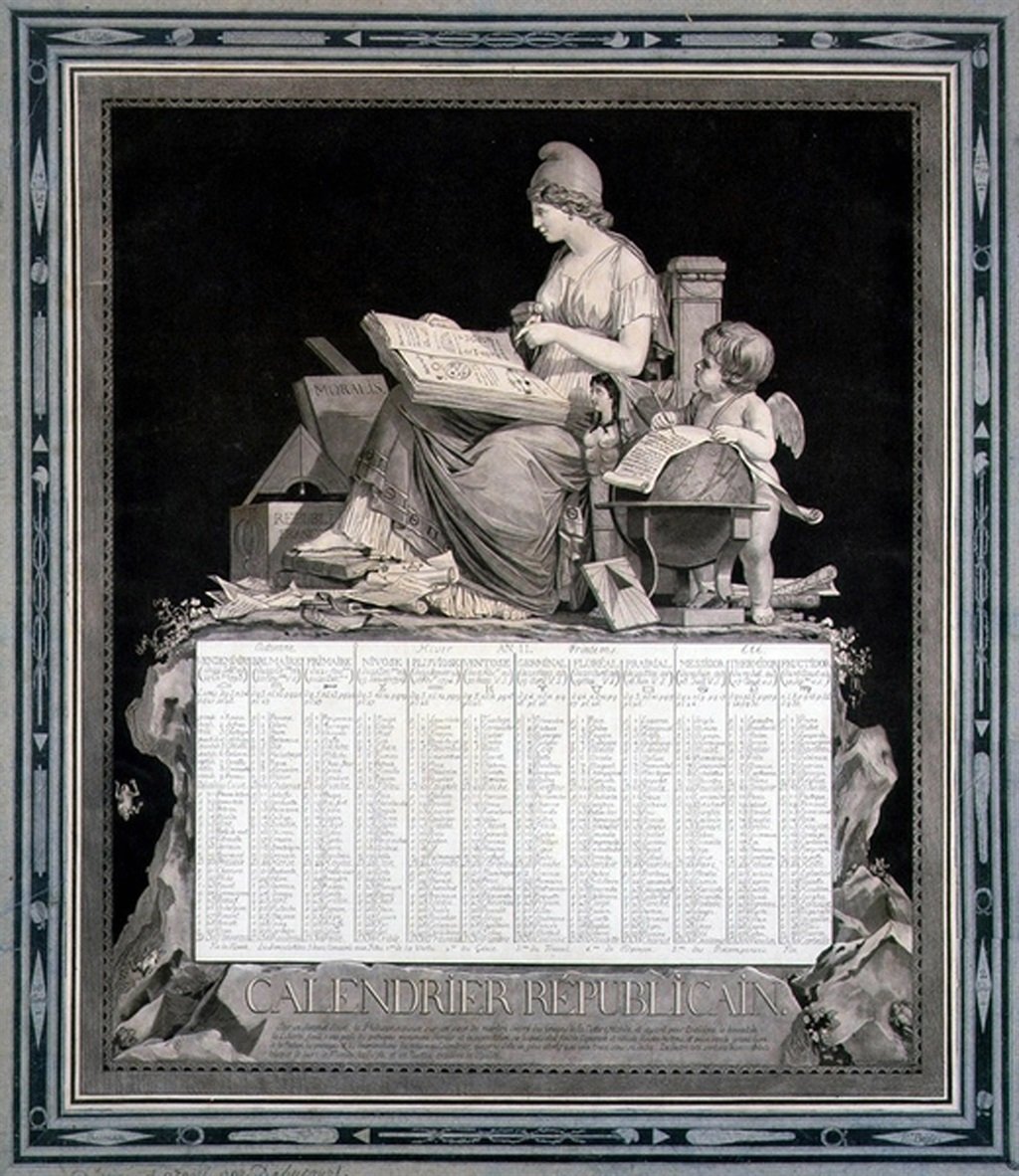

That question was asked with particular vehemence in the 18th century by so-called enlightened thinkers, and was brought to a head in the French Revolution. In 1793, the revolutionary government regularised the month to a standard 30 days (each with three weeks of ten days), leaving a messy five to six unallocated days a year, and giving workers only three days off each month. The start of the year was shifted to the autumn equinox, because an égalité (equality) of light and dark was a symbol of the new republic’s ideals.

The calendar was a victory of reason, if reason is align with simplicity, clarity and the number of our fingers. But, as we have seen, in astronomical terms nature is stubbornly unreasonable. The system was short-lived.