Painting is an ancient medium that has remained a consistent means of expression despite the emergence of photography, film, and digital technology. So many paintings have been limned over dozens of millennia that only a small percentage of them may be considered as “timeless classics” that have become familiar to the public—and not coincidentally produced by some of history’s most famous artists.

Of course, we have our own preferences, which we share in our list of the best paintings of all time.

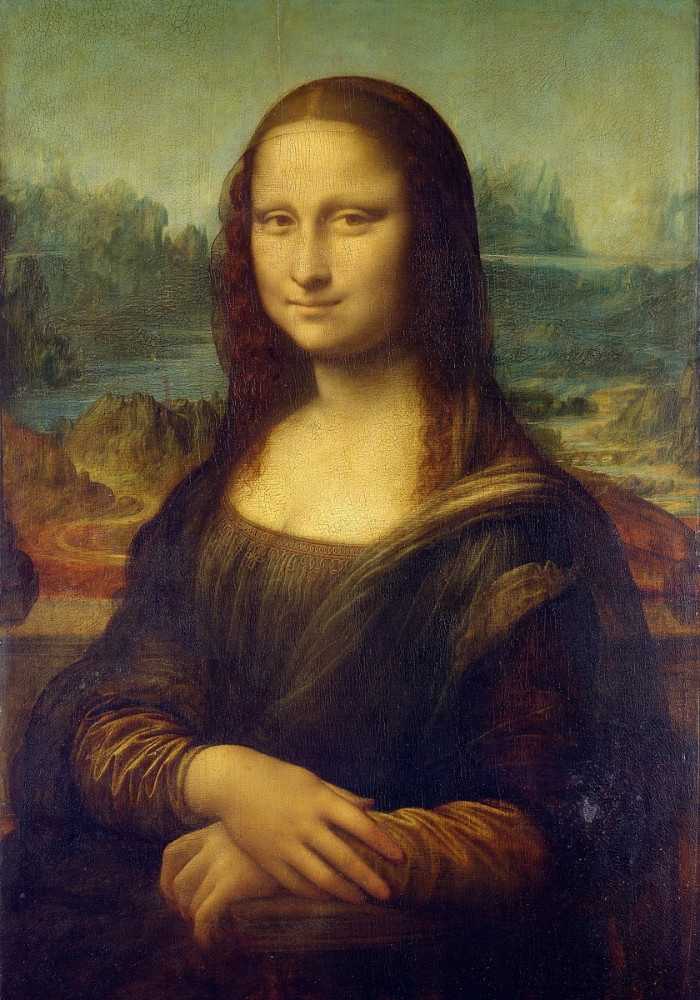

1. Leonardo Da Vinci, Mona Lisa, 1503–19

Painted between 1503 and 1517, Da Vinci’s alluring portrait has been dogged by two questions since the day it was made: Who’s the subject and why is she smiling? A number of theories for the former have been proffered over the years: That she’s the wife of the Florentine merchant Francesco di Bartolomeo del Giocondo (ergo, the work’s alternative title, La Gioconda); that she’s Leonardo’s mother, Caterina, conjured from Leonardo’s boyhood memories of her; and finally, that it’s a self-portrait in drag. As for that famous smile, its enigmatic quality has driven people crazy for centuries. Whatever the reason, Mona Lisa’s look of preternatural calm comports with the idealized landscape behind her, which dissolves into the distance through Leonardo’s use of atmospheric perspective.

2. Johannes Vermeer, Girl with a Pearl Earring, 1665

Johannes Vermeer’s 1665 study of a young woman is startlingly real and startlingly modern, almost as if it were a photograph. This gets into the debate over whether or not Vermeer employed a pre-photographic device called a camera obscura to create the image. Leaving that aside, the sitter is unknown, though it’s been speculated that she might have been Vermeer’s maid. He portrays her looking over her shoulder, locking her eyes with the viewer as if attempting to establish an intimate connection across the centuries. Technically speaking, Girl isn’t a portrait, but rather an example of the Dutch genre called a tronie—a headshot meant more as still life of facial features than as an attempt to capture a likeness.

3. Vincent van Gogh, The Starry Night, 1889

Vincent Van Gogh’s most popular painting, The Starry Night was created by Van Gogh at the asylum in Saint-Rémy, where he’d committed himself in 1889. Indeed, The Starry Night seems to reflect his turbulent state of mind at the time, as the night sky comes alive with swirls and orbs of frenetically applied brush marks springing from the yin and yang of his personal demons and awe of nature.

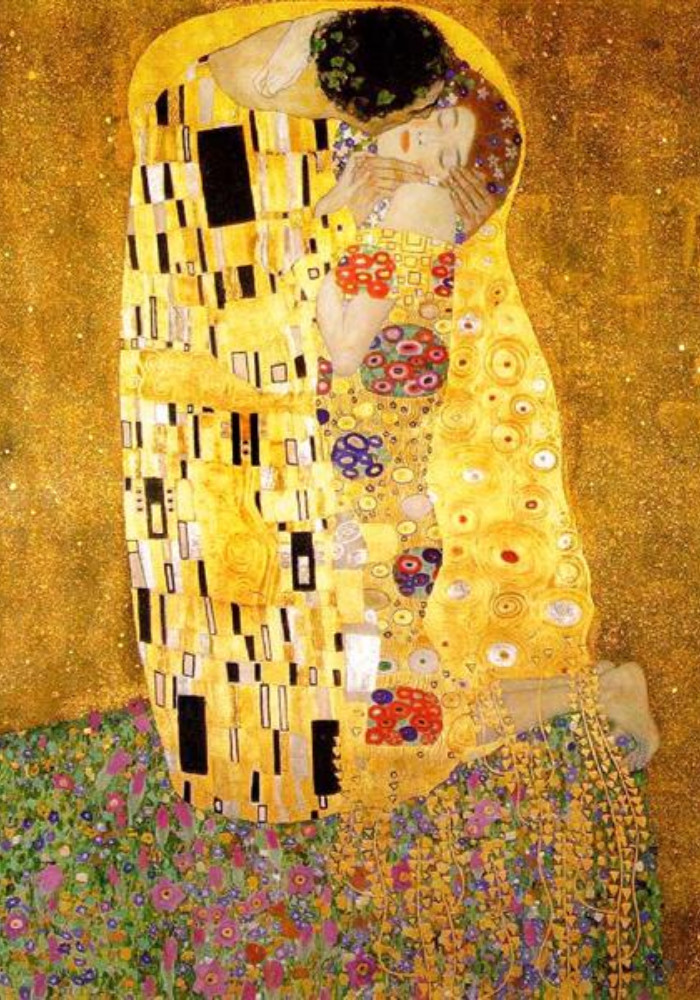

4. Gustav Klimt, The Kiss, 1907–1908

Opulently gilded and extravagantly patterned, The Kiss, Gustav Klimt’s fin-de-siècle portrayal of intimacy, is a mix of Symbolism and Vienna Jugendstil, the Austrian variant of Art Nouveau. Klimt depicts his subjects as mythical figures made modern by luxuriant surfaces of up-to-the moment graphic motifs. The work is a highpoint of the artist’s Golden Phase between 1899 and 1910 when he often used gold leaf—a technique inspired by a 1903 trip to the Basilica di San Vitale in Ravenna, Italy, where he saw the church’s famed Byzantine mosaics.

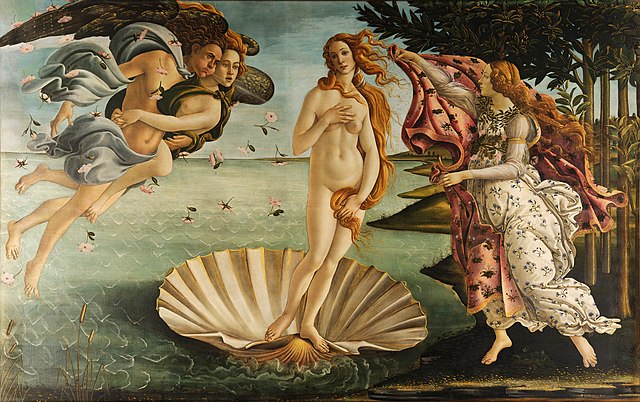

5. Sandro Botticelli, The Birth of Venus, 1484–1486

Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus was the first full-length, non-religious nude since antiquity, and was made for Lorenzo de Medici. It’s claimed that the figure of the Goddess of Love is modeled after one Simonetta Cattaneo Vespucci, whose favors were allegedly shared by Lorenzo and his younger brother, Giuliano. Venus is seen being blown ashore on a giant clamshell by the wind gods Zephyrus and Aura as the personification of spring awaits on land with a cloak. Unsurprisingly, Venus attracted the ire of Savonarola, the Dominican monk who led a fundamentalist crackdown on the secular tastes of the Florentines. His campaign included the infamous “Bonfire of the Vanities” of 1497, in which “profane” objects—cosmetics, artworks, books—were burned on a pyre. The Birth of Venus was itself scheduled for incineration, but somehow escaped destruction. Botticelli, though, was so freaked out by the incident that he gave up painting for a while.